Samnite Warriors, in ReposeThe rise of Rome, from a small town on the seven hills flanking the river Tiber, in central Italy, to the Great Empire it became is a story that has enthralled historians, ancient and modern to their very core. What was unique about this particular city, and its people, that propelled the Romans to rule great swathes of western Europe, and southern Europe, together with the Middle East, the Balkans and north Africa? Rome in 400 BC did not appear particularly special amongst the many warlike peoples of central Italy. But first, there are other matters to contemplate.

Although Greek civilisation was at its zenith, in 400 BC, it had suffered and survived a series of bitterly contested internecine wars, as well as wars against the Persian empire and the Carthaginians. Its greatness, fostered by the fierce independence of the city-state system was ultimately responsible for its downfall. Greece was never a nation and though the Greek cities were bound by language and strong cultural ties, there was never a unity that would allow the Greeks to found and rule over an empire. It is true they would forge leagues and alliances. These leagues formed for defensive and offensive reasons were too fragile to provide true unity- they were always subject to the turbulent flow of Greek politics and changing expediencies. In the end, fractured city-state politics were to be exploited by a semi-barbarous Greek kingdom to the north. Macedonia would bring forth unity and coherence by means of the sword and the skilful manipulation of Greek politics (338 BC). But it would always be a Macedonian Empire. The Greek cities could never overcome their fierce and innate independence and could never really come to terms with the 'political reality' imposed from without. It took the cohesive genius of Phillip and thereafter, Alexander, to force the Greeks to become partners in the empire to come.

It will always remain a mystery, that after conquering and securing the Persian Empire, Alexander became obsessed with expansion, further east, unto mysterious lands. His army was none too keen and it was their reluctance to continue that would define the eastern limit of his Empire in 324 BC. In hindsight, his persistence was an insane vainglorious adventure not predicated upon sound military or logistical foundations. It seems odd that he never contemplated, turning west, once Persia was conquered. During his exotic bellicose peregrinations, he left one formidable enemy unbloodied and unsullied, 'Westward ho'-, the Carthaginians.

The Carthaginians hailed originally from the city of Tyre, Phoenecia, and were supposedly founded by an exotic queen/bint with astonishingly acute/astute/cute tailoring skills, sometime in the 9th century BC. Apparently, according to myth and folklore, she was named, Dido. This wayward/seaward seafaring folk made land on the North African shore, in what is now, Tunisia, sometime after teatime. Anyway, it twas an astute colonial possession/progression, and the city they founded was named, rather unimaginatively, 'New City' (Carthage). The relatively civilised Punes (a Greek rendering) soon dominated the barbarous tribes of the hinterland and founded dependent cities along the North African coast. As time went forth, the Carthaginians began to quarrel with the equally land grabbing/grubbing Greeks, especially over possession of the island of Sicily. Eventually, and after much blood-letting, there followed an uneasy truce, leaving the Greeks in possession of the eastern parts, whilst the Carthigininains held the west (265 BC).

And thus, I have set the stage for the entrance of the Romans (stage left). Eventually, the Romans would take over all the Hellenes had built. This was not apparent to Alexander or to his immediate successors, of the time. The Romans were slow and steady on their way to greatness, however, and regardless, their initial succession, albeit sluggish, was inexorable and sure-footed. Certainly, the Carthaginians didn't see them coming.

By, 290 BC the Romans were well on the way to their conquest of Italy and were left unmolested by the Greeks until Roman expansion threatened the Greek diaspora in southern Italy. In 282 BC they came into dispute with the Greek city of Tarentum. A notorious Greek king and freebooter, Pyrrhus of Epirus, a nephew of Alexander the Great, decided to intervene on behalf of his Greek cousins. He amassed an army and confronted, and defeated, the Romans at Heraclea (280 BC) in southern Italy. Pyrrhus, like all Greeks, thought of none Greeks as barbarians, Romans included. However, it is said that he was impressed by the Roman army's camp disposition and orderliness. While in hostile territory, Roman soldiers constructed a fortified night camp with a ditch, earthworks and a palisade. On seeing the industrious Romans constructing their camp, Pyrrhus remarked: "funny, they don't act like barbarians". The Macedonian general was able to defeat the Romans once again at the battle of Asculum (279 BC). Both battles were hard fought and costly. It seems that Pyrrhus was not without an ironic sense of humour and exclaimed: "another victory like this one and I will be going home alone" (Pyrrhic Victory). A final battle ensued, in which the Greeks were defeated at Benventium in 275 BC. Pyrrhus had had enough of his Italian adventure and decided that there was more profit to be obtained elsewhere. And so he left his southern Greek allies to their fate. This garrulous Greek offered a final prediction. As he was embarking with his army from Sicily, he declaimed: "what a wonderful wrestling ground we are leaving to the Romans and Carthaginians." It is a great shame I don't have the space to write about this energetic, and generally underrated, Greek soldier/king, in this series of posts. Anyway, he came to an ignominious end after being struck by a roof tile in Argos, in 272 BC. Worthy of another series, perhaps?

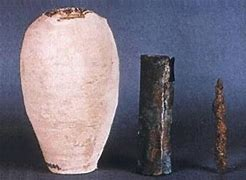

At this juncture, it will be useful to consider how the Roman army of the time of the Second Punic War (218 BC-202 BC), was organised and armed. For most folk when they think of the Roman army, they imagine a truly professional set-up. In truth, the army only became the professional edifice of modern conception with and after the Marian reforms (107 BC). Prior to the Marian reforms, the Roman army, was very like Greek armies, in that it was a militia formed by citizens who could afford to equip themselves, with arms. The army would be raised for a campaign and disbanded once the hostilities concluded. Originally, the army was armed and fought very much like the Greek hoplite. After a series of wars with a hill people (Samnites) of central Italy (ended 304 BC), the Romans found that their mode of fighting was too inflexible in broken hill country and adapted their equipment and way of fighting accordingly. The Romans were always happy to adopt ideas from their enemies if it suited and ancient writers declare that the Romans copied the Samnite shield (Roman scutum). However, other sources state that the Romans had adopted the scutum at an earlier time. From now on the battle order was more open, and small units of men could operate independently (maniple- 120 men). They also arranged the army into three battle lines: the first line consisted of the youngest class of citizens (hastati); the second line (Principes) contained men in their prime, and the third line was formed of grizzled, battle-hardened veterans (triarii).

By 272 BC the Romans had conquered most of the Italian peninsula and were about to embark on their first overseas adventure that would set their course to becoming a Great Empire. It was in 264 BC that the Romans decided to meddle in Scillian affairs during which they came into conflict with the Carthaginians. Two glorious wars later, ending in 202 BC, the Romans had control of Sicily, the Mediterranean islands of Sardinia and Corsica, together with most of the Spanish peninsular. Carthaginian power was forever broken and the city was destroyed in 176 BC by the Romans and former Carthaginian territories in north Africa were annexed.

This will do for now. I consider this post as an introduction to the 'Roman Way of War'; why were the Romans so successful and how have they influenced the Western Way of conducting war up until the modern era? This will of course represent the final post on the 'On War' series unless I decide otherwise.

`